After Diem Was Killed the North and South Vietnam United as One Country Again

Prologue: The Cease of the "American War"

On April xxx, 1975, the concluding of America'due south wartime personnel in South Vietnam boarded crowded boats and helicopters in a frantic attempt to abscond the country. That aforementioned day, North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon. The palace was the seat of the Southward Vietnamese government, which the Americans had supported and the N Vietnamese had fought against. When North Vietnamese officers entered the palace, S Vietnam'southward president told them he was ready to manus over power. They reportedly replied, "Yous cannot give upward what you do not accept."i

The Vietnam War, or what is known in Vietnam equally the Resistance War against the Americans, was over.

Image one: North Vietnamese tanks crashing the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon, 1975.

Image one: North Vietnamese tanks crashing the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon, 1975.

The war's cost was immense. The country'south infrastructure was ravaged by bombing and landmines, and parts of its otherwise lush landscape had been stripped by toxic chemicals like Agent Orangish. As many as two million civilians died in the conflict, along with 1.iii million Vietnamese soldiers. Most of these soldiers died fighting for or alongside Northward Vietnam.ii Just for all the losses North Vietnam had to absorb, its authorities and its allies in the due south had reason to experience triumphant. They had "prevailed against all odds," says historian Christopher Goscha, first chirapsia the French in a violent war of de-colonization, then beating the Americans in one of the most vicious conflicts of the Cold State of war.3

Introduction: The Challenges of Reconciliation

Ceremonious wars issue from, and sometimes deepen, divisions within societies. As Goscha observes, those divisions do non but disappear once the fighting stops.iv This was the case in Vietnam. Although some people in Due south Vietnam welcomed reunification and "liberation," non everyone shared the feeling of triumph. For some, the war's end raised uncomfortable questions: What kind of authorities would they take? Would the south have autonomy from the communist northward? And what would happen to the people the communists viewed as enemies, such as capitalists and those who were associated with the South Vietnam regime and its American or French backers?

The fall of Saigon in 1975 paved the manner for the long-awaited reunification of Vietnam. But reconciliation—"healing the wounds and divisions of a society in the aftermath of sustained violence"—was a bigger challenge.five One thing continuing in the way of reconciliation was the North Vietnamese government's deep suspicion of many people in the south and their doubts about southerners' loyalty to the communist regime. As volition be discussed later, its approach to building a sense of loyalty was oft heavy-handed and often had the effect of alienating people rather than winning them over.

The story of Vietnam after the war can exist told from many different perspectives. Here, nosotros focus on ane of those perspectives: that of the southerners who were fabricated to experience that their lives before 1975 were a offense that needed to be punished, or a sin for which they needed to atone. We expect at how they responded to life under a new system; some adapted, some found safe ways to resist, and some decided that their best or just hope was to leave to make a new life elsewhere. We also look at the dramatic changes that take taken identify in Vietnam since economic reforms were introduced in 1986— changes that, according to recent surveys, take made Vietnam one of the most optimistic societies in the world. The changes have been so dramatic that Vietnam is now luring dorsum some of the people who left—people who believed that mail-war Vietnam had nothing to offer them.

Background: The Road to War and Partition

In May 1975, the Due north Vietnamese government faced the daunting task of stitching back together a country torn autonomously by decades of war. This rupture had its roots in the menses of French colonization (1858–1954), a bitter feel for the vast majority of Vietnamese that gave ascension to various pro-independence movements. The virtually significant of these was the Indochinese Communist Party created by nationalist leader Ho Chi Minh in 1930. During the Second Globe War, the Japanese occupied Indochina, but kept the French in identify to administer Vietnam. Meanwhile, in 1941, Ho Chi Minh secretly created the Vietnamese Independence League, called the Viet Minh, but did not have an opportunity to seize ability until 1945. In March of that yr, the Japanese overthrew the French in Indochina, but and then so surrendered to the Allies 5 months afterwards. The surrender created a power vacuum that allowed the Viet Minh to seize power in the northern city of Hanoi. On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared the country's independence, naming it the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

France, however, was not willing to give up its profitable colony. From 1946 to 1954, information technology fought the Viet Minh in a disharmonize now referred to as the First Indochina State of war. At kickoff, the French had the upper hand, but the Viet Minh wore them down, dealing them a decisive blow in 1954 in the Boxing of Dien Bien Phu. Presently after that, the earth'southward major powers opened negotiations in Geneva, Switzerland, to effort to bring an end to the war.

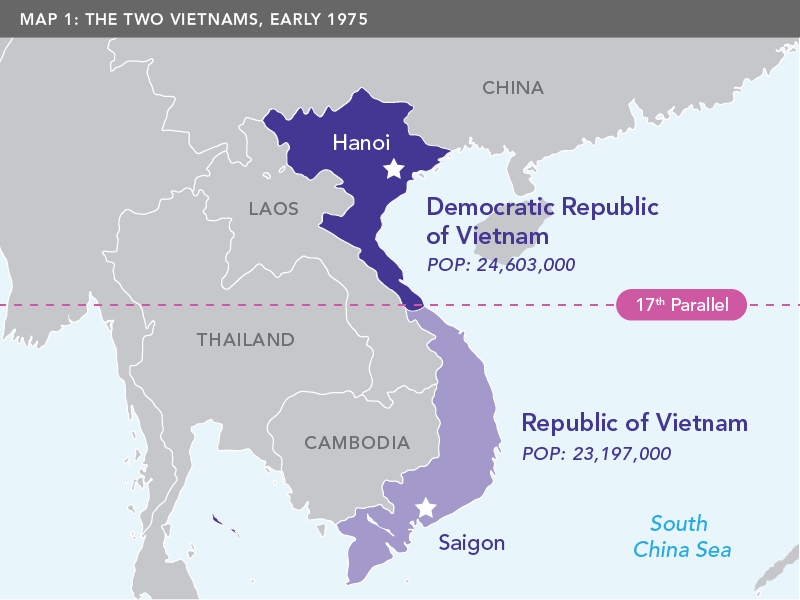

In that location were two outcomes of the Geneva Conference. First, a ceasefire ended the state of war betwixt French republic and the Autonomous Democracy of Vietnam; however, this besides resulted in the land beingness divided at its "waist" (the 17th parallel) (see Map one). Ho Chi Minh's communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam took command of the zone to the n of the 17th parallel, while the Country of Vietnam, created by the French in 1949 and increasingly supported by the Americans, administered the south. This partition was intended to be temporary.

The second outcome was an agreement by the two Vietnams to hold elections in 1956. These elections, it was believed, would unite the country under 1 of the 2 governments (Ho Chi Minh was heavily favoured). But this was not to be. In 1955, an anti-communist nationalist in the south named Ngo Dinh Diem transformed the State of Vietnam into the Republic of Vietnam and opposed unification with the communist north. 6 The existence of two Vietnams was at present more than entrenched: a communist N Vietnam and an authoritarian non-communist S Vietnam.

Map 1: The 2 Vietnams, Early 1975.

Map 1: The 2 Vietnams, Early 1975.

Past 1960, a ceremonious war was brewing, peculiarly after the Due north created the National Liberation Front (NLF), a political organization and army, better known as the Viet Cong, in the south. The NLF included both communists and non-communists, and its purpose was to bring downwards the Ngo Dinh Diem regime and unify the country on the North's terms. Every bit the Viet Cong expanded its command over the south, the U.Southward. responded by sending more military machine directorate. Worried that Ngo Dinh Diem was failing to stop the communists from taking over, U.South. President John F. Kennedy supported the South Vietnamese military's overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963. Neither Diem nor Kennedy would survive the year. Diem was assassinated past his ain war machine on November 2, 1963, and Kennedy was killed in Dallas 3 weeks later.

Following Kennedy's assassination, Lyndon Johnson became the new U.S. president. In 1965, the United states of america intervened directly in Vietnam by sending troops to South Vietnam. The 2d Indochina War—likewise known as the American State of war—had begun; it would not end until the United States withdrew and South Vietnam fell to the communist-run Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1975.

Consolidating Political Control

The N and its allies' defeat of the Republic of Vietnam cleared the way for the long-awaited reunification of the country. Soon afterwards that, the North Vietnamese regime took several steps to consolidate its political control over the south. This included eliminating potential rivals, "re-educating" those who were suspected of disloyalty, and preventing other ideologies and beliefs from competing with socialism.

Removing rivals: The North quickly fabricated clear that previous agreements for sharing power with allied groups in the south were no longer valid. According to the 1973 Paris Peace Accords (another set of negotiations that aimed to bring an end to the conflict), South Vietnam "was supposed to continue to exist every bit a separate and sovereign state" until the northerners and the southerners could agree on how to "unite the two Vietnams via elections or negotiations."7 Several NLF leaders believed that they could carve out and maintain some sort of neutral, non-communist southern state. At kickoff, they had reason to be optimistic: the North had made repeated promises "that they were in no rush to communize the south."8

Epitome 2: Viet Cong soldiers waving NLF flag.

Epitome 2: Viet Cong soldiers waving NLF flag.

But in the weeks after liberation, there were already signs that the Northward would non tolerate an culling base of power, especially 1 that included not-communists similar the NLF. 1 superlative NLF official named Truong Nhu Tang reflected on this while watching the victory parade organized by the communists shortly afterward they took Saigon. Rather than carry the NLF flag, his troops (divisions) were carrying the Democratic Republic of Vietnam flag, the flag of North Vietnam. He says:

Seeing this, I experienced almost a physical shock. Turning to Van Tien Dung who was and then standing next to me, I asked quietly, "Where are our divisions one, three, five, 7, and nine?" Dung stared at me a moment, then replied with equal deliberateness; "The regular army has already been unified"…"Since when?" I demanded; "At that place's been no determination about anything similar that." Without answering, Dung slowly turned his eyes back to the street, unable to suppress his sardonic expression, although he must take known it was conveying too much. A feeling of distaste for this whole matter began to come over me—not to mention premonitions I did non want to entertain.9

At a meeting of northern and southern delegates in the summertime of 1976, the decision was fabricated official: the 2 Vietnams would be merged into a single land, called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The conclusion was fabricated without any meaningful word or contend. Some southern delegates objected, saying that people in the south would not easily have life in a socialist system, but their protests were not heeded.10

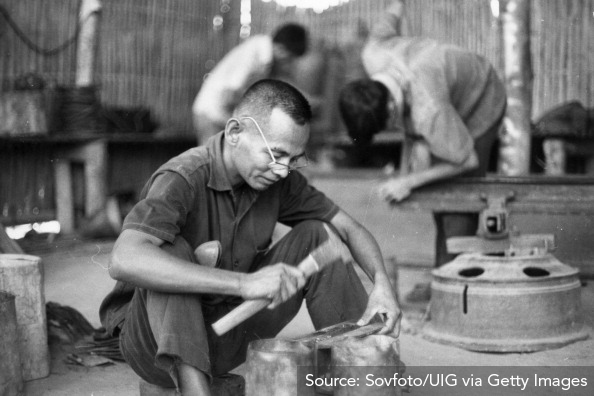

"Re-educating" people: Many low- and mid-level ceremonious servants in the quondam South Vietnam government were replaced past officials from the north. Most of these officials had done work that was not particularly political in nature, like running a schoolhouse or hospital. But they were still required to spend a few days or weeks in "retraining courses," in which a

communist cadre advisedly explained to his listeners their errors [and] provided them with the fundamentals of a new communist society, peppering his lecture with liberal citations from the internationalist Marxist canon and Ho Chi Minh. He then repeated the importance of following the correct path before letting everyone go. 11

For soldiers and college-ranking officials in the South Vietnam government, and for anyone else viewed with suspicion, "re-teaching" was longer and more severe. Some people spent several years in camps. They were subjected to torture and brainwashing and forced to do hard labour in inhospitable areas of the state. Some who were taken away to the camps were never seen over again.12 In total, near a one thousand thousand people in the one-time South Vietnam were subjected to some form of "re-teaching."

Epitome 3: Vietnamese homo in a re-education camp (other camps were more like prisons).

Epitome 3: Vietnamese homo in a re-education camp (other camps were more like prisons).

Some southerners described their fourth dimension in these camps as the start fourth dimension they interacted with northerners in many years. Tran Tri Vu, who spent four and a one-half years in vi re-education camps, describes this in his memoir, Lost Years:

Our generation in the South was suddenly charged with wrongdoing considering we had not lived in the North, had not been used to the mode of reasoning of the Northern people, had not accepted their ideology. Our peel was the same color, we spoke the aforementioned language, our indigenous origin and geographic location were the same, and yet we were completely dissimilar from them. When Northern soldiers poured into the Southward, they had appeared to our eyes as country folks who had strayed into a big town…Living in their company, observing their way of life and thinking, and specially experiencing our treatment in the camp, we had come up to realize that between usa and them was a barrier that could never exist overcome. 13

Finding the "bad elements": One tool the government used to identify so-called "bad elements"—those who were opposed to the North's communist ideology—was the personal dossier. These were written biographies that included a person's proper noun and the names of his or her family unit members, as well as his or her ethnicity, religious affiliation, and current job. The government used this information to categorize people as "skilful" or "bad." If a person had a sister, father, or uncle who had worked with the French, American, or South Vietnamese government, for example, he or she would likely be put in the "bad" category. Similarly, if someone's family owned a business or other belongings, it meant that person was a capitalist, which was besides bad. In full, the number of people who were believed to have such affiliations was estimated to be i-third of the south's population.14

People from families that had shown loyalty to the communist cause and liberation—specially those with a family member who died fighting Southward Vietnam and/or the Americans—were usually put in the "practiced" category. Unlike the "bad elements," these people had opportunities under the new organisation, such every bit getting a good job working for the authorities or armed forces, or better admission to a academy education.15

Monitoring and silencing alternative forms of thinking and belief: The media, schools, and religious institutions were brought under government command. All of these represented potential challenges or alternatives to socialism and were therefore seen as threats. Newspapers were shut downward and the government started keeping records of who attended religious services. The authorities was especially suspicious of Christianity, which information technology saw as a holdover from the colonial years. Only even non-European religions like Buddhism were viewed with suspicion. Some religious buildings were airtight downward or required to place a portrait of Ho Chi Minh on their altars.sixteen The government also burned books that information technology felt were not supportive of the revolution, and it replaced many teachers in the south with teachers from the northward, who they believed would be more loyal.

Building a Socialist Economy

In addition to consolidating political command, the Vietnamese government introduced a socialist, centrally planned economic system in the south. (This system was already in place in the north.) In such economies, people are often discouraged or forbidden from owning private property. Instead, belongings is "collectively" owned and controlled by the government, which makes decisions about what to produce and how much to distribute to different groups. Introducing this system in the south led the government to take several deportment:

Cracking downwards on commercialism: The government confiscated (took away) private property from its owners and "nationalized" (took command of) many southern businesses. One of the groups well-nigh affected was the indigenous Chinese minority, known as the Hoa. Many Hoa in the south profited during the period of French colonization, and connected to play a major role in South Vietnam's capitalist economic system. Yet, they more often than not avoided politics and refrained from aligning themselves also closely with the S Vietnamese regime.

Nevertheless, by the tardily 1970s two events made the Hoa a target: declining economic policies, which fabricated them a user-friendly scapegoat; and the Vietnam regime's deteriorating relationship with China.17 Co-ordinate to Goscha, 70 percent of the capitalists who were targeted in the post-war period were Chinese.eighteen The scale of their losses was staggering, estimated at US$2 billion.19 As journalist Barry Wain commented in 1979, harassing the Hoa and confiscating their property benefited the government in two ways: it removed resources from a group it suspected of disloyalty; and it profited from the assets information technology confiscated, including, says Wain, "considerable quantities of gilded that [had] been buried in backyards since the communist takeover."20

De-urbanizing the population: The population of cities like Saigon swelled in size during the war as people fled the fighting and bombing in rural areas. After reunification, the regime worried these cities would get sites of social unrest, and it encouraged people to return to their hometowns. Some did then voluntarily, simply others were relocated against their volition to New Economic Zones (NEZs) gear up by the government. These zones were commonly located in remote highland areas, where living weather condition were harsh. According to one account:

people were transported to the NEZs and told to produce crops with no equipment guidance. The people received no food and were reduced to eating the leaves off the trees and bushes. There were well known cases of people [in] the NEZs dying from eating manioc leaves that they had cooked. 21

Many people "escaped or bribed their way back to the city [and the] new economical zones came to be widely perceived every bit places of internal exile."22 In add-on, many of the highland areas where NEZs were set upwardly were inhabited by Vietnam's indigenous peoples, and they generally did not welcome outsiders who viewed them as "backwards and uneducated."23

Collectivizing peasants: Almost half of all rural families in the south were organized into agricultural collectives. These collectives put several families together into a single unit that was expected to combine what they produced and turn over any surplus (anything above what they needed for their bones and immediate consumption) to the government. The government distributed this surplus to people elsewhere in the country. In collectivized farming, people were rarely rewarded individually for their difficult work. Thus, while collectives were supposed to make the rural economic system more productive, they often had the opposite result. Says Goscha: "collectivizing agriculture and setting uncompetitive prices … erased incentives for production in the countryside. Rather than producing more, Vietnamese peasants … but cultivated plenty land upon which to live rather than take to turn over whatsoever surplus to the state at fixed prices (i.e. at a loss)."24

Epitome 4: Vietnamese peasants.

Epitome 4: Vietnamese peasants.

With decreasing productivity, the economy contracted. By the late 1970s, Vietnam, once a major rice producer, was experiencing cases of dearth or near famine. Information technology was becoming clear that the socialist economical experiment in the south was failing.

Resistance and Escape

Southerners were non entirely passive in responding to these changes. Some accepted and adapted to life under the new system, whereas others found "safety" ways to push button back, especially against the new economic arrangement (although there were no safe means to push back against the political system). Others chose to get out, even when doing then was fraught with danger and doubtfulness.

Everyday resistance: Some peasants who were forced to bring together rural collectives resisted in ways that were quiet and indirect. They did this in order to avoid punishment, a tactic anthropologist James Scott calls "weapons of the weak." This includes pocket-size but persistent deportment or inactions by those who lack formal power to push back against those who have formal ability. These "everyday forms of resistance" included, for example, not putting forth one's full endeavor to produce for the commonage in gild to save time and energy to grow food for i'south own family. Some other case was delaying delivery of grain or livestock to government authorities.25 These tactics became increasingly common, and by the early 1980s in that location was a noticeable "southern resistance" to collectivized agriculture.26 It should also exist noted that peasants in the n were as well using these resistance tactics, and many somewhen withdrew from collectives.

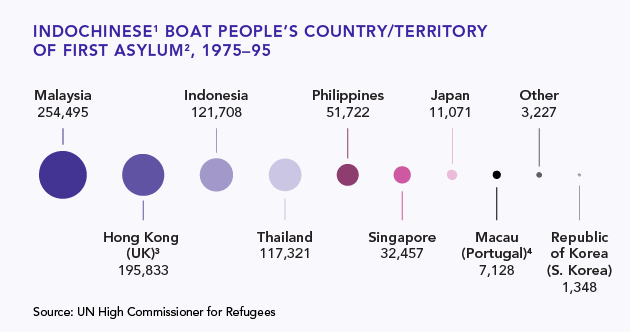

Fleeing Vietnam: Some who were targeted by the authorities, or who generally faced worsening atmospheric condition, made the decision to exit. The first moving ridge of departures was the 140,000 southerners who fled during the autumn of Saigon in 1975. These were people who had worked with the Americans, and most were permanently re-settled in the The states. Merely the departures continued, even without American or other international assist. Smaller numbers continued to get out Vietnam, many in small and rickety boats that landed in neighbouring countries or territories where they requested asylum. In 1977, approximately 15,000 Vietnamese "boat people" had arrived in Southeast Asian countries. Past the terminate of the following yr, the numbers reached alarming levels, quadrupling to 62,000.27 An estimated lxx per centum of them were ethnic Chinese.28

By 1979, members of the international community were recognizing that the situation had become a humanitarian crisis. In that location were two main reasons for their concern. The first was the refugees' safety and welfare. About 10 percent of the "boat people" died at sea because of drowning, attacks past pirates, a lack of food and water, or disease due to the poor conditions on their boats. Many more barely survived. The United nations Loftier Commissioner for Refugees, Poul Hartling, called it "an bloodcurdling human being tragedy."

Image v: Gunkhole people from Vietnam.

Image v: Gunkhole people from Vietnam.

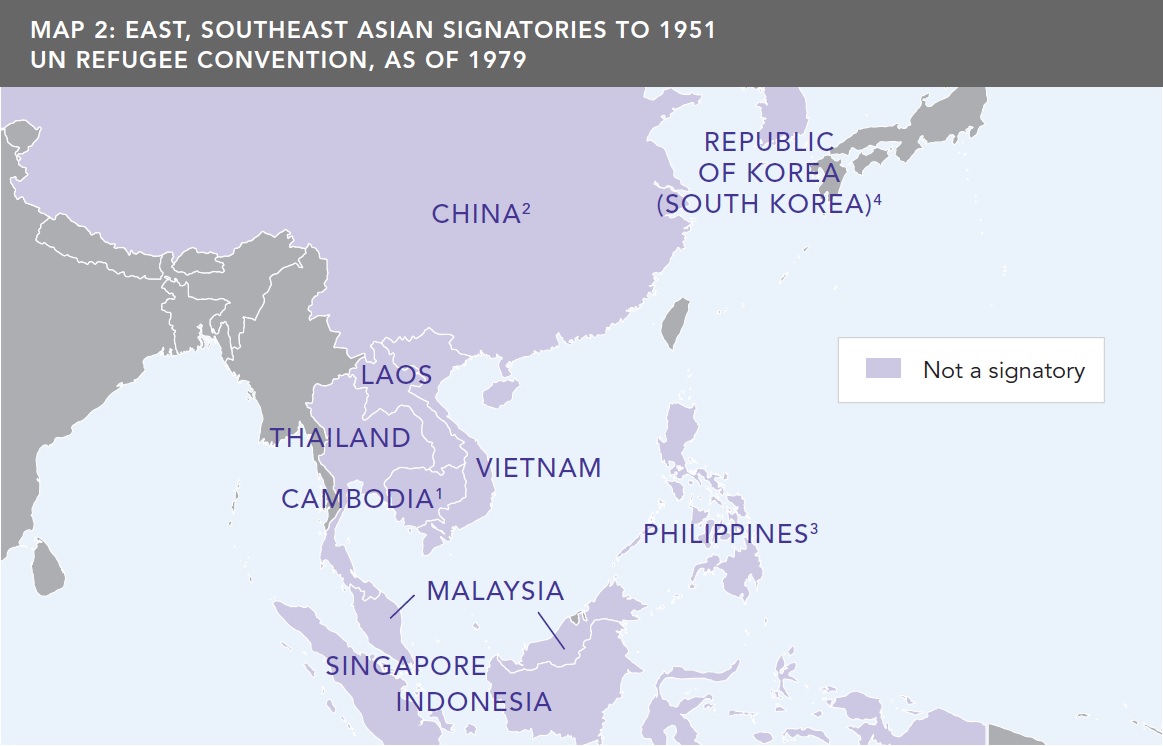

The 2nd issue was the uncertainty about where these refugees could exist resettled. The countries where they sought first asylum—that is, the places where they landed get-go—were mostly in Southeast Asia. But none of these countries had signed the United nations 1951 Convention Relating to the Condition of Refugees. Therefore, they had no legal obligation to grant asylum.29 As such,

None of the countries receiving Vietnamese gunkhole people gave them permission to stay permanently and some would not even permit temporary refuge. Singapore refused to disembark [allow to go ashore] any refugees who did not have guarantees of resettlement [in other countries] within 90 days. Malaysia and Thailand frequently resorted to pushing boats away from their coastlines. When Vietnamese boat arrivals escalated dramatically in 1979, with more than 54,000 arrivals in June alone, boat 'pushbacks' became routine and thousands of Vietnamese may have perished at sea equally a result. At the finish of June 1979 … Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand … [announced] that they had "reached the limit … and would not have any new arrivals". 30

Similarly, there were reports of refugee boats in distress existence neglected by other ships passing them, violating the "fundamental dominion of the sea that passing ships must terminate to rescue people from vessels in trouble."31

Map 2: East, Southeast Asian Signatories to 1951 UN Refugee Convention, equally of 1979.

Map 2: East, Southeast Asian Signatories to 1951 UN Refugee Convention, equally of 1979.

In response, the United Nations organized an emergency meeting to observe a solution to the immediate crisis. What resulted was a three-manner understanding:

- Country of origin (Vietnam): Those fleeing Vietnam were so desperate to leave that they resorted to using illegal means. They frequently had to bribe police and edge agents to allow them to go out, and had to sell almost all their valuables in club to pay smugglers to go them out of the country.32 In near cases, these officials and smugglers were not primarily concerned with the safety of the refugees. Therefore, as part of the new UN agreement, Vietnam agreed to the Orderly Departure Program, which involved taking measures to make these departures safe, orderly, and legal.

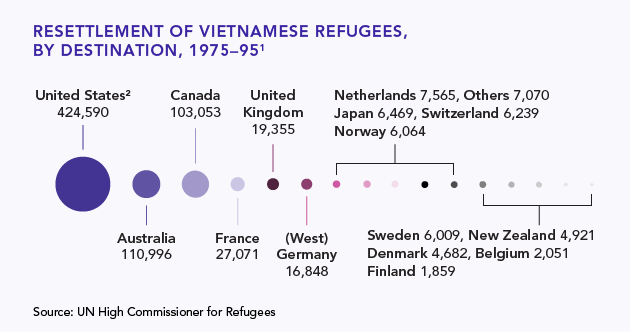

- Countries of resettlement: At the fourth dimension of the United nations meeting, but about 9,000 Indochinese refugees per month were being permanently resettled—a step far slower than what was needed to keep up with the number arriving in neighbouring countries and territories. Australia, Canada, France, and the United States led a group of more than xx countries in speeding upwardly the procedure to 25,000 per month (see Figure i). From July 1979 to July 1982, these countries settled virtually 625,000 refugees fleeing disharmonize not only in Vietnam, but too in Cambodia and Lao people's democratic republic.33

- Countries of first aviary: The five Southeast Asian countries that had been the site of commencement asylum for many of the boat people (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) agreed to provide temporary asylum under ii conditions: that Vietnam implement the Orderly Difference Programme, and that other countries act more than quickly to provide the refugees permanent homes (encounter Figure ii).

Figure 1: IndoChinese Boat People's Country/Territory of First Aviary, 1975-95.

Figure 1: IndoChinese Boat People's Country/Territory of First Aviary, 1975-95.

Figure 2: Resettlement of Vietnamese Refugees, past destination, 1975-95.

Figure 2: Resettlement of Vietnamese Refugees, past destination, 1975-95.

These measures did non totally end the "boat people" crunch, but they did assistance to prevent an even larger humanitarian crisis that was brewing by the late 1970s. Nevertheless, says Goscha, this "internal hemorrhaging" of Vietnamese lodge "was proof that national reconciliation," until that point, "had been a failure."34

Putting Post-War Vietnam in Context

For any country recovering from years of ceremonious war, stabilizing and rebuilding can be overwhelming. Vietnam's power to practice this was slowed past two boosted challenges. The commencement was economic; after withdrawing from the country in 1975, the U.s. imposed a trade embargo on Vietnam, "cutting off the war-wrecked state not only from Us exports and imports, but as well from those of other nations that bowed to American pressure level." In add-on, the Usa pressured other international bodies to deny assist to Vietnam.35

The 2nd challenge was geopolitical. Two weeks earlier Vietnam's reunification, the government in neighbouring Kingdom of cambodia was overthrown by the Khmer Rouge, a communist regime oftentimes described as genocidal and murderous. Although both countries were led by communist governments, members of the Khmer Rouge leadership were suspicious of Vietnam, believing that information technology wanted to expand its control over Cambodia. The Central khmer Rouge began launching attacks against Vietnam along their shared edge. In 1977, Vietnam retaliated with military strikes of its own, and past late 1978, began a more vigorous assault on the Khmer Rouge. In January 1979, information technology overthrew the Khmer Rouge and replaced it with a authorities that was more than favourable toward Vietnam. Afterwards that year, People's republic of china, as penalty for the overthrow of its ally, the Khmer Rouge, "launched a brief attack on several northern provinces on Vietnam."36 These two conflicts were part of a larger grouping of conflicts known equally the Third Indochina War.

Withal, pointing the finger at these other governments did not assist Vietnam solve the practical economic difficulties it was facing internally. Following reformist policies being adopted in China and the Soviet Matrimony, Vietnam'due south communists launched market-oriented economical reforms that prepare the land on a course for major changes.

Doi Moi and the "New" New Vietnam

Past the early 1980s, Vietnam's government was coming to realize that communism would non provide a phenomenon cure for chop-chop modernizing the state and growing its economy.37 As Goscha observes, "raw peasant hunger brought the Viet Minh to power in August 1945," and information technology could too bring down the communists fifty years later.38 In 1986, Vietnam introduced a series of market reforms chosen doi moi ("renovation"). Central planning was abased and the economy was opened upward to market forces of supply and demand. In rural areas, the government ended collectivization and allowed farmers to go along what they grew and sell it at markets.39 Rice product rebounded dramatically, making Vietnam one of the world's largest rice exporters. Exports of tea and coffee also grew significantly. In the cities, new factories began producing items like shoes, clothes, and computers that would exist sold in other countries.twoscore By 2001, Vietnam's economy was growing chop-chop at about 8 percent per twelvemonth.

Epitome half dozen: Vietnamese peasants selling their goods at a marketplace.

Epitome half dozen: Vietnamese peasants selling their goods at a marketplace.

Although the benefits of doi moi have been uneven, with some benefiting more than than others, almost everyone has seen improvements in their lives. For example, at the cease of the war, lxx percent of the people in Vietnam were living below the official poverty line. Today, that number is estimated to be less than twenty pct. And Vietnam's literacy rate is now an impressive 95 per centum. The reforms have also raised the status of some southerners, especially those with business skills; whereas they were once labelled "bad elements" because of their connectedness with capitalism, the regime came to encounter them as playing an important role in boosting the country's economy.41

Of class, doi moi has had some downsides. In improver to growing social and economic inequality, corruption (including by members of the ruling Communist Party) has become a serious problem. In addition, at that place take been no corresponding reforms of the political system. Still, there are at least two signs that many Vietnamese people both within and exterior the country recognize as positive.

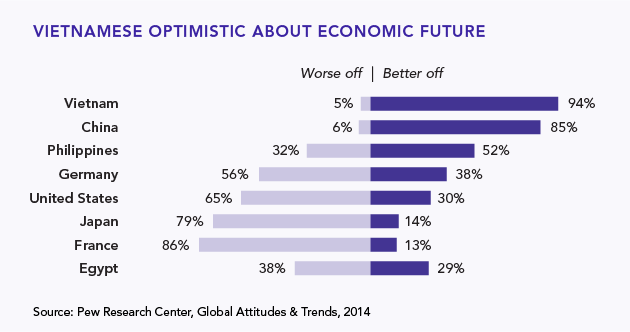

Optimism about the Future: In 2014, a survey of 44 countries (both developing and adult) asked people if they thought their children would exist amend off or worse off financially than themselves. Vietnam outranked every other state in its optimism well-nigh the time to come, with 94 percent maxim they believed their children would exist better off (come across Figure iii). The aforementioned survey asked people: "What would you recommend to a young person who wants a expert life, staying or moving abroad?" Lxxx-viii percent of people in Vietnam said "staying" (see Effigy iv) a stark difference from the fashion and so many felt in the late 1970s.42

Figure 3: Vietnamese Optimistic nigh the Next Generation'southward Economic Future.

Figure 3: Vietnamese Optimistic nigh the Next Generation'southward Economic Future.

Figure iv: Vietnamese see more reasons to stay than leave.

Figure iv: Vietnamese see more reasons to stay than leave.

Return of Overseas Vietnamese: Some of the people who left Vietnam 40 years ago are now returning. The aforementioned is truthful of some of their children, who have grown upwardly in countries like Australia, Canada, France, and the United States. Their understanding of Vietnam has been shaped from the outside, including by their parents and grandparents who may have left under sorry circumstances. Whatsoever they may accept learned from their elders, they are lured by a sense that they can benefit from Vietnam's energy and apace growing economy. This (re)connection with the Viet kieu (overseas Vietnamese) has been encouraged past the Vietnamese government, which hopes these overseas Vietnamese will bring investment and the types of capitalist businesses the communists one time disapproved of so strongly. The return migration has also been facilitated by Vietnam'due south re-establishment of relations with its one-time adversary, the United States, and other western countries the Viet kieu have chosen dwelling.

Although the political system has been much slower to open up up, the Vietnamese government, still run past the Communist Party, seems to accept learned the lesson that many other ruling communist parties also learned: that 1 way to win over your population is by giving them less collectivization and "re-education," and more opportunities to enjoy the same things that people in other countries enjoy, like cars, smartphones, and family unit vacations.

Vietnamese Youth: Writing the Next Affiliate

Image 7: Vietnamese youth on a motorcycle in Hanoi.

Image 7: Vietnamese youth on a motorcycle in Hanoi.

As noted earlier, the wounds inflicted during civil wars have a long time to heal. Has Vietnam healed those wounds and finally achieved reconciliation between northerners and southerners? The optimism Vietnamese people feel well-nigh their future suggests that the war may not be the most important issue for a bulk of the country's people. Indeed, the survey mentioned above suggests a state that is looking alee more than information technology is looking to the past. When Barack Obama visited the country in 2016, the U.S. president's comments reflected this mood equally he spoke to a crowd in the capital city of Hanoi. "This is your moment," he said, assuring them that as they pursued the future they wanted, the United States—the country that fought Vietnam for more than two decades —would be right there along with them.43

But on the issue of the war, there are all the same lingering differences between northern and southern perspectives:

For older Vietnamese, the war and its aftermath are emotional topics remembered and recounted with selective detail. Southerners, for example, tend to be familiar with and sympathetic to the perilous, often tragic feel of the boat refugees, an exodus in which, by some estimates, every bit many as 300,000 people perished at sea. Northerners, on the other paw, sometimes bear witness only a vague awareness and express a harsh viewpoint, some calling those who left cowards who abandoned Vietnam in hard times. 44

What exercise younger Vietnamese think? The answer to this question is significant; almost 70 pct of the country's population was born afterward the state of war, and their memories of that flow of the country'due south history are mostly inherited from their parents and grandparents, or learned through what they are taught in school. In fact, the post-state of war generation is "the first generation since French colonialism to take been raised during a time of independence and peace."45 Many urban youth tell international reporters that they are non that interested in learning about the war, and would adopt to spend their time doing the kinds of things that young people in other countries like doing, such as riding skateboards, shopping with friends, hanging out in cafes, and making plans for where they will written report abroad—all things that are available to them thanks to the economic reforms and opening up afforded by doi moi.

These benefits, however, oft feel out of achieve for many rural youth. While the reforms that accept been underway since 1986 have by and large benefited Vietnam as a whole, information technology is clearly the case that urban, well-connected families have benefited much more than. This includes members of the government. This is not to advise that rural Vietnamese are more than cached in the by than their urban counterparts; it may suggest, still, that a new division is starting to open in Vietnamese lodge—non betwixt north and south, merely rather betwixt those who are experiencing Vietnam'southward economic success and vivid hereafter and those who are nonetheless aspiring to it.

Acknowledgement

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) is grateful to Christopher Goscha, professor of history at the University of Quebec at Montreal, who provided helpful comments and suggestions in developing this background reading. Professor Goscha is the author of two recent books on Vietnamese history: The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam (Penguin UK, 2016) and The Making of Modern Vietnam (Bones Books, 2016).

APF Canada is responsible for the content of this background reading.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Province of British Columbia through the Ministry building of Education.

Finish Notes:

For a total list of citations, please come across the PDF version of this document.

Source: https://asiapacificcurriculum.ca/learning-module/vietnam-after-war

Post a Comment for "After Diem Was Killed the North and South Vietnam United as One Country Again"